As a global community we have been consuming more and more meat, partially driven by an increase in world population but also from increased affluence, and this is leading to larger pressures on our biodiversity and greater emissions. More of the land is being converted from natural ecosystems, such as tropical rainforests, to grazing land or crop land for animal feed. And then there is the very serious problem of methane emissions. Methane has a much greater warming effect in our atmosphere than carbon dioxide but its lifetime is relatively short-lived. That means that reductions in methane are probably our most powerful lever in our attempts to limit climate change over the next decade, and all methane reduction projects are to be welcomed and this includes us all eating less meat.

In this article we are not trying to advocate for universal vegetarian or vegan diets, but encourage a reduction of meat consumption to help look after our planet and its biodiversity. In the past, eating meat was generally reserved for feast days and special occasions unless you happened to be royalty or very wealthy indeed. Our knowledge of food and nutrition now means that some of the healthiest diets and meals are entirely plant-based. With governments and health experts advocating more fresh vegetables (e.g. the well-advertised 5-a-day campaign in the UK, encouraging 5 or more servings of vegetables and fruit each day) and a growing awareness of the health risks of high red meat and processed meat diets, shifting the balance of what is on our plates from meats to vegetables seems both sensible and cost-attractive.

Contribution to climate change

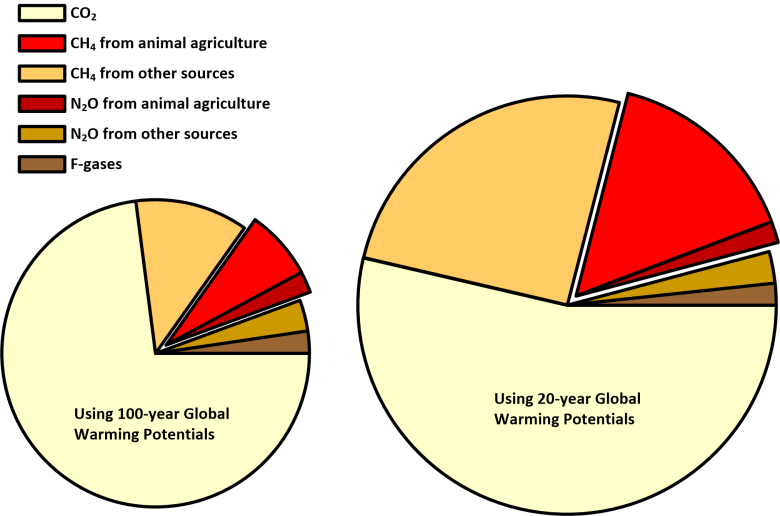

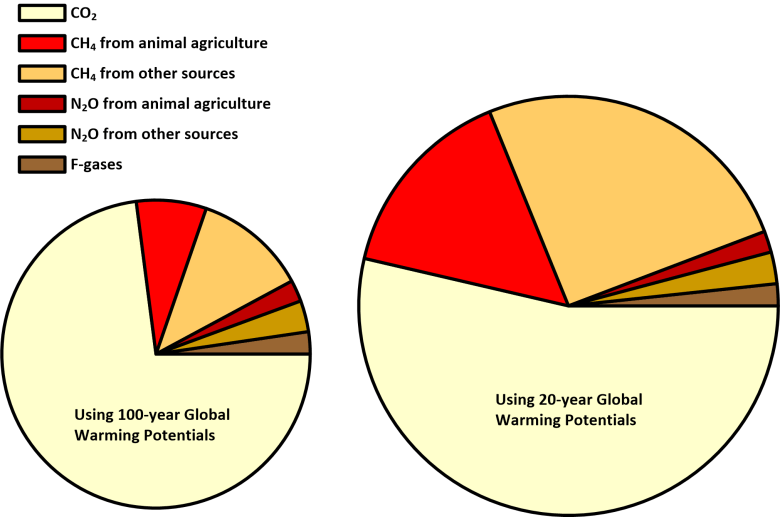

The amount of methane and carbon dioxide emitted from different human activities is fairly well understood and the concentration of these gases in the atmosphere is very carefully measured. Comparing the effect of methane emissions to carbon dioxide emissions is not straightforward due to the shorter time methane persists in the atmosphere before it breaks down producing carbon dioxide. Methane traps many times more heat than carbon dioxide. So comparisons must consider a timespan over which the warming effect is calculated. The convention in most climate science is to make the comparison over a 100-year window: comparing the average warming potential of methane over 100 years (during which time it has broken down into carbon dioxide) with that of carbon dioxide over the same 100 years. However, with the emphasis on reduction of global warming in the shorter term to meet 2050 goals (and to reduce the accelerated increase in atmospheric concentrations to reduce the risk of inducing or triggering climate tipping points such as methane release from melting permafrost), an increasing number of commentators are preferring to use the 20-year equivalence window which attributes larger short-term warming effects to methane than when using the 100-year comparisons.

Contribution to biodiversity loss

In land use terms, livestock farming requires large areas of land. This is both traditional pastureland or cropland specifically for animal feed. It comes as little surprise that livestock farming is a major pressure on some of our endangered ecosystems. For example, 41% of deforestation is attributed to beef production and is by far the biggest contributor compared to any other commodity.

A plant-based diet turns out to require a smaller land area than a meat-based diet. Perhaps as small as one hundredth of the area (assessed for both calories and protein).

Our choice

When we consider our own carbon footprint (the emissions associated with our lifestyle and choices) and our land use footprint (the area of land associated with lifestyle and choices) then for many of us, reducing our meat consumption is one of the single most effective personal actions we can take to play our part in getting to net zero and protecting the remaining biodiversity hot-spots. This is particularly true if we don’t own property or private transportation.

If you seek inspiration for plant-based meals then there are some good recipe books now available at most good bookshops. Or you could look at our own meat-free recipes on the Food Zone of this website.

Further reading

Global Methane Budget, scientific information portal hosted on Global Carbon Project, 2024

Meat and Dairy Production from Our World In Data, last updated 2023.

World Health Organisation review of red and processed meats from an environmental and health perspective, 2023.

World Health Organisation health concerns with red and processed meat, 2015.

WWF easy read on deforestation

Drivers of deforestation from Our World In Data, last updated 2024.